Apparent Earth Pressures in Excavation Design

- Dec 17, 2025

- 9 min read

A Comparative Assessment Using LEM Analysis

Introduction

The use of apparent earth pressure diagrams remains a cornerstone in the design and verification of retaining systems, especially for excavations supported by sheet piles, soldier piles, or diaphragm walls. Traditional approaches such as the Active Earth Pressure Method (Rankine or Coulomb), Peck’s Apparent Pressure Envelope (Peck, 1969), and the FHWA Apparent Pressure Method (O’Rourke and Clough, 1990) provide valuable insights into the distribution of lateral loads acting on excavation support systems. While numerical models and finite element analyses are increasingly common, the Limit Equilibrium Method (LEM) remains a practical and transparent tool for assessing wall behaviour and performing safety verifications.

In this context, DeepEX software offers a robust platform that integrates LEM, apparent pressure methods, and Finite Element Method (FEM) analyses within a unified modelling environment. This enables consistent comparison of traditional and numerical design approaches under identical boundary conditions, allowing engineers to directly evaluate the influence of different earth pressure assumptions on wall performance. This article revisits the relevance of using apparent pressure envelopes in conjunction with LEM-based design and includes an FEM analysis for comparison, highlighting differences in predicted wall loads, bending moments, and support reactions across the various methods.

Model Description

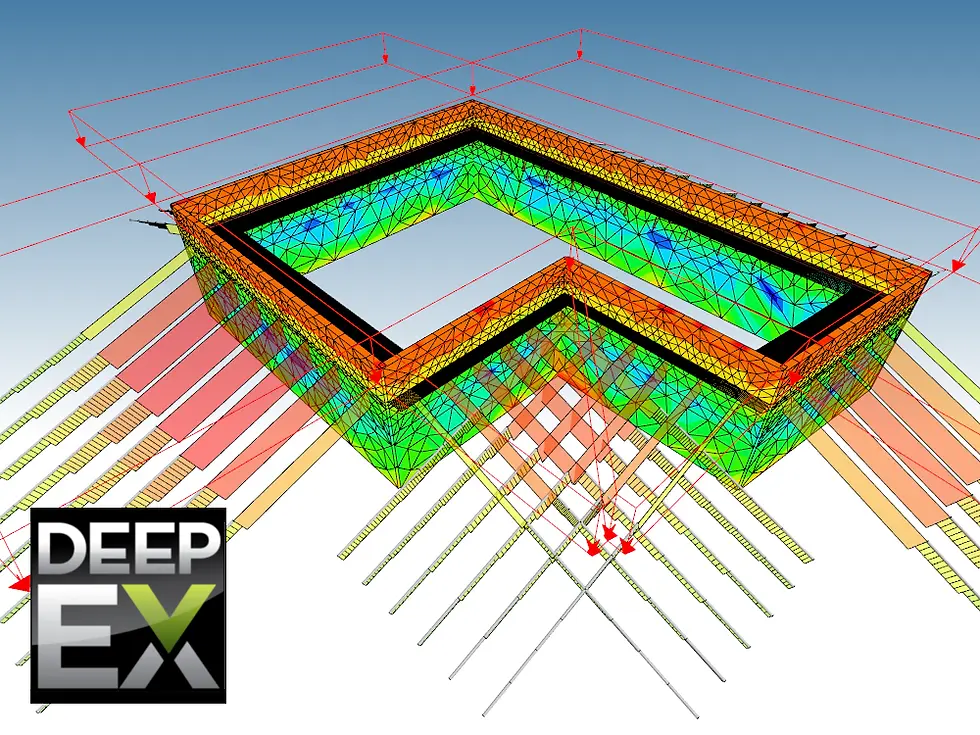

The case model used for this analysis (Figure 1) represents a 9 m-deep braced excavation supported by a steel sheet pile wall, analysed using the Limit Equilibrium Method (LEM). The analysis captures both the geotechnical and structural interaction between the retaining wall, the support system, and the stratified soil profile under short-term conditions.

The soil stratigraphy adopted for the model comprises four main layers, as follows:

· F – Fill layer: Unit weight γ = 19.6 kN/m³, friction angle ϕ′ = 30°, elastic modulus E = 14,700 kPa. This thin surficial layer represents recent fill or loose topsoil with limited shear strength contribution but relevant for defining surface loading and boundary conditions.

· S1 – Upper granular/weathered layer: Unit weight γ = 21 kN/m³, friction angle φ′ = 34°, elastic modulus E = 25,000 kPa. This layer provides moderate stiffness and lateral resistance, contributing to the mobilization of active pressures in the upper portion of the wall.

· Clay (UND) – Intermediate cohesive layer: Unit weight γ = 20 kN/m³, undrained shear strength su = 150 kPa, elastic modulus E = 20,000 kPa. The clay layer governs short-term stability and wall deflection behaviour, representing the critical stratum for basal stability assessment.

· GT – Lower granular layer: Unit weight γ = 22 kN/m³, cohesion c′ = 10 kPa, friction angle ϕ′ = 36°, elastic modulus E = 30,000 kPa. This competent granular deposit provides a firm base for the sheet pile embedment and contributes to overall passive resistance.

The groundwater table is located approximately 6.0 m below ground level, influencing effective stress distribution along the retained side of the excavation.

The retaining system consists of steel sheet piles analysed as an elastic beam (AZ 26 section, section modulus = 2600 cm³/m, yield strength fy = 344.8 MPa) with three levels of tieback anchors with 1.5 vertical and horizontal spacing positioned along the depth of the excavation, prestressed to 80% of the maximum experienced load per level (applied at the activation stage). The analysis incorporates three different methods for determining driving lateral earth pressures — the Active Earth Pressure Method, Peck’s Apparent Pressure Diagram (1969), and the FHWA Apparent Pressure Envelope (GEC 4, 1999) — to compare their influence on predicted wall loads, bending moments, and overall system stability.

Figure 1 – Model Geometry and Soil Stratigraphy (built in DeepEX).

Methodology

Three earth pressure distributions were applied, within the same framework in DeepEX software, to the same geometry and boundary conditions:

Active Earth Pressure (Rankine): Based purely on soil strength parameters (c’, ϕ', γ) and wall height, assuming active conditions behind the wall.

Peck (1969) Apparent Pressure Diagram: Derived from field measurements of braced excavations, this method accounts for wall–soil interaction and redistribution of loads after deformation, offering a more realistic representation of pressures in flexible retaining systems.

FHWA Apparent Pressure Envelope: Incorporates both empirical observations and design conservatism, refining Peck’s approach by relating pressure magnitudes and distribution to soil type, wall stiffness, and excavation geometry.

Each pressure distribution was applied as the driving pressure in the LEM model, allowing direct comparison of wall moments, shear, and support reactions under each condition.

In addition, a Finite Element Method (FEM) analysis was performed in DeepEX using the same geometry, soil profile, and staged excavation sequence. This provided a benchmark for assessing soil–structure interaction effects and deformation-dependent load redistribution not captured by LEM-based approaches. The inclusion of FEM results enables a direct comparison between conventional apparent pressure methods and a fully numerical simulation within the same computational environment.

Results and Discussion

The comparison presented in Figure 2 highlights the contrasting behaviour of the wall under different earth pressure assumptions — Active pressures, Peck’s (1969) apparent envelope, FHWA apparent pressures, and a Finite Element Method (FEM) analysis. The Active pressure method predicts the lowest driving loads and bending moments, representing a lower-bound scenario that assumes sufficient wall movement to fully mobilize active conditions. This results in a narrow pressure envelope and smaller bending moments concentrated near mid-depth. In contrast, the Peck (1969) apparent pressure distribution generates higher and more uniform pressures along the retained height, particularly within the clay layer.

Figure 2 – Earth Pressure Distribution Diagrams (Active, Peck, FHWA, and FEM)

The FHWA envelope, based on updated field data and design recommendations (FHWA-NHI-14-007, 2014), yields slightly reduced pressures compared to Peck’s diagram while maintaining a similar overall shape, providing a rational balance between conservatism and realism. Finally, the FEM results reveal a more complex, non-linear pressure profile, with distinct peaks at each strut level and reduced pressures between supports — reflecting the actual soil–structure interaction and stress redistribution in a braced excavation. The corresponding bending moments are also more distributed and lower in magnitude than those predicted by empirical envelopes. Overall, this comparison reinforces the value of using apparent pressure methods, particularly FHWA’s, to complement analytical and numerical approaches, ensuring that wall designs account for both theoretical limits and observed field performance.

· The active pressure distribution resulted in the lowest overall load on the wall, reflecting minimal mobilization of passive resistance. While this approach provides a baseline, it may underestimate design loads for flexible walls or multi-level bracing systems where deformation allows load redistribution.

· In contrast, Peck’s apparent pressure yielded a more uniform load profile with higher mid-depth pressures, aligning with observed field behaviour for soft to medium clays. The apparent maximum pressure was approximately 30–40% greater than that predicted by the active earth pressure model.

· The FHWA envelope produced results intermediate between the two, offering a balanced design perspective. It captured higher loads near the top struts, where deformation is restrained, and reduced pressures at depth, consistent with modern monitoring data.

· When comparing bending moments, the active pressure case produced the smallest maximum moment (about 40–50% lower than the apparent pressure methods). Both Peck and FHWA methods resulted in similar peak moments, though FHWA predicted slightly higher values near the top strut level due to its non-uniform pressure distribution.

Figure 3 presents the variation of support reactions with excavation stage for the three apparent earth pressure models, incorporating the effects of prestressed tieback anchors. The results demonstrate a progressive increase in reaction forces as the excavation advances and successive anchors are installed and mobilised. The Active earth pressure model continues to produce the lowest reactions, reflecting its assumption of full active mobilisation and lower lateral loads. Conversely, both Peck’s (1969) and FHWA apparent pressure envelopes predict higher reaction forces, particularly in the middle and lower excavation levels, which aligns with the expected load redistribution in flexible, multi-level anchored systems. The inclusion of prestress in the tieback anchors results in higher initial reaction values and a smoother progression of load mobilisation, improving overall stability control and reducing excessive wall deflection. Among the apparent pressure models, the FHWA envelope produces slightly higher support reactions at shallower depths, capturing the combined influence of prestress and non-uniform pressure distribution consistent with modern field measurements.

Overall, apparent pressure envelopes better represent the redistribution of soil pressures in flexible retaining systems, providing more reliable internal force predictions for strut and wall design.

Table 1 summarises the principal design outcomes for the different earth pressure models, including maximum wall moment, shear, support reaction, and embedment stability. The results confirm that the assumed pressure distribution strongly influences both structural demand and global stability assessments. The Active earth pressure model produces the lowest wall moment and shear values, consistent with its reduced driving loads and idealised mobilisation of active conditions. In contrast, the Peck (1969) and FHWA apparent pressure methods yield higher wall moments and support reactions, representing more realistic load transfer to the supports. Between these two, the FHWA envelope predicts a slightly higher critical support check value and embedment factor of safety, indicating a more balanced and conservative performance envelope. The FEM analysis, which captures soil–structure interaction and deformation effects, produces the largest wall bending moments but lower maximum support reactions, reflecting redistribution of loads through wall flexibility. Overall, these comparisons emphasise that apparent pressure-based LEM analyses, particularly using the FHWA approach, provide a practical yet conservative representation of anchored wall behaviour when detailed numerical modelling is not required.

Figure 3 – Support reaction per stage

Table 1 – Summary of Wall Design Results (Max. Pressure, Max. Moment, Tieback anchor Forces)

Method | Wall Moment (kN-m/m) | Wall Shear (kN/m) | Wall Displacement (cm) | Max Support Reaction (kN/m) | Critical Support Check | Embedment Wall FS |

Active pressures | 19.49 | 45.7 | --- | 77.8 | 0.383 | 5.816 |

Peck apparent | 33.27 | 69.84 | --- | 88.03 | 0.401 | 5.435 |

FHWA apparent | 19.22 | 49.36 | --- | 87.88 | 0.432 | 5.964 |

FEM | 79.46 | 51.6 | 3.84 | 70.96 | 0.286 | N/A |

Figure 4 presents the distribution of wall bending moments with depth for the different earth pressure assumptions—Active, Peck (1969), FHWA, and FEM. The results clearly illustrate how the assumed pressure distribution affects the magnitude and shape of the moment profile along the wall.

The Active Earth Pressure model generates the smallest bending moments, concentrated near mid-depth, consistent with its lower driving pressures and assumption of full active mobilization. In contrast, Peck’s (1969) and FHWA apparent pressure diagrams produce larger and more distributed moments, particularly between the upper and middle strut levels where lateral pressures are highest. The two apparent pressure methods yield comparable profiles, though the FHWA envelope predicts slightly higher bending near the top strut, reflecting its non-uniform pressure distribution and accounting for restrained wall movement.

The FEM analysis shows a distinctly different trend, with a smoother and broader moment curve. Maximum bending occurs around mid-depth but with a more gradual variation, indicating redistribution of loads through wall flexibility and staged support mobilization. The peak bending moment from FEM is approximately two to three times greater than those predicted by the apparent pressure methods, though its overall shape aligns well with observed field behaviour in braced excavations.

Overall, the results in Figure 4 confirm that apparent pressure-based LEM analyses provide realistic yet conservative estimates of wall bending behaviour, bridging the gap between idealized active pressure theory and fully coupled numerical modelling.

Figure 4 – Wall Bending Moment Profiles for Different Earth Pressure Methods (Active, Peck 1969, FHWA, and FEM)

Conclusions

This study highlights the continued relevance of apparent earth pressure diagrams in the assessment and design of braced and anchored excavations. When incorporated into LEM-based analyses, these diagrams provide practical and realistic insights into wall behaviour, particularly where detailed numerical modelling may not be warranted.

Key findings from the comparative assessment include:

· Active earth pressure theory provides a useful lower-bound estimate of wall loads but tends to underpredict bending moments and support reactions, particularly in flexible systems where full active mobilisation is unlikely.

· Apparent pressure methods, such as those proposed by Peck (1969) and the FHWA (GEC 4, 1999), offer more realistic load distributions that better reflect field-measured performance of multi-level braced and anchored excavations.

· Support reaction analyses, accounting for tieback prestress, show that the FHWA envelope produces slightly higher and more evenly distributed reactions at upper support levels, representing the combined effects of prestress and staged load mobilisation.

· Wall response comparisons indicate that the Active and FHWA models yield the lowest bending moments, while Peck’s envelope produces higher mid-depth demands. FEM analysis predicts greater bending but lower peak support reactions, evidencing load redistribution through wall deformation.

· The summary of wall design results confirms that the FHWA approach provides a balanced and conservative design basis — achieving realistic internal forces, satisfactory stability margins, and compatibility with observed field trends.

An important advantage of the adopted modelling framework is the capability of DeepEX to perform comparative analyses using different earth pressure methods within a unified environment. This allows direct comparison of wall moments, shear forces, and support reactions under consistent boundary conditions and geometry, ensuring that variations in results are solely attributable to the assumed pressure distributions rather than modelling inconsistencies. Such functionality enhances the reliability of design assessments and provides valuable insight into the sensitivity of wall behaviour to different design assumptions.

Overall, the integration of apparent pressure methods within LEM frameworks remains a reliable and efficient approach for preliminary and verification analyses of supported excavations. The FHWA envelope, in particular, offers a rational balance between empirical experience, conservatism, and modern design practice, reinforcing its applicability in current geotechnical design standards.

References

Peck, R.B. (1969). Advantages and Limitations of the Observational Method in Applied Soil Mechanics. Géotechnique, 19(2), 171–187.

O’Rourke, T.D. & Clough, G.W. (1990). Construction and Performance of Excavation Support Systems. ASCE Special Publication 25.

FHWA-NHI-10-024 (2010). Earth Retaining Structures. Federal Highway Administration, Washington, D.C.

NAVFAC DM-7.02 (1982). Foundations and Earth Structures. U.S. Department of the Navy.

Let us show you how to reduce your design time by up to 90%!